Faculty of Science researchers are connecting traditional knowledge holders with students to help decolonize and indigenize research, courses and curricula.

The Department of Ocean Sciences' Dr. Annie Mercier and her team of students and post-doctoral fellows developed new learning opportunities and are conducting fieldwork in Nunavut in collaboration with Inuit communities, to do just that.

Sea cucumber conservation efforts are one of the main focuses of the fieldwork a species that Inuit communities harvest for food.

The organisms are also essential for nutrient recycling, making them vital to the ocean's health and balance.

Dr. Mercier is spearheading these conservation efforts in her role as co-chair of the IUCN SSC Sea Cucumber Specialist Group.

As part of her work with the IUCN Species Survival Commission, she attended the fifth Leaders Meeting last fall. She was also invited to lead the publication of Revered and Reviled: The Plight of the Vanishing Sea Cucumbers last month in Annual Reviews of Marine Science.

The paper not only underscores the critical role that sea cucumbers play in marine ecosystems, it explores bottlenecks management and conservation efforts face worldwide.

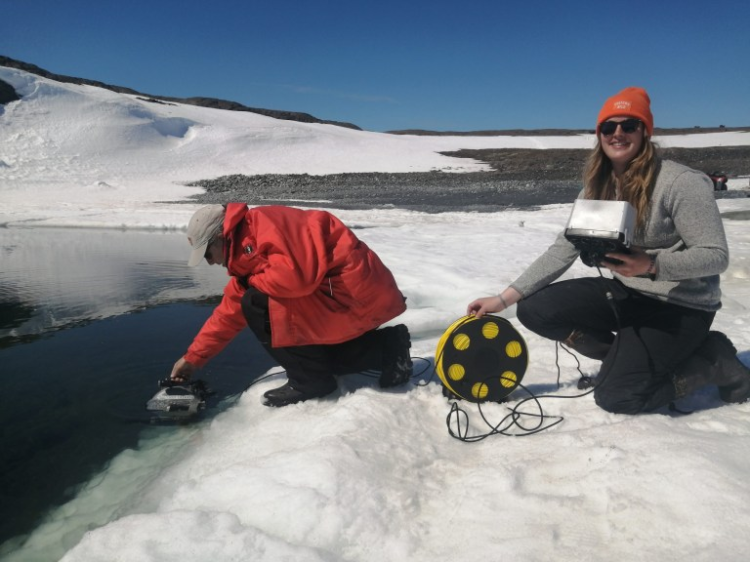

Arctic research conducted by the Mercier lab in Qikiqtait, Nunavut, involves the use of a portable remotely operated vehicle. Here, it is handled by team members from the June 2022 expedition. From left are Dr. Annie Mercier's husband Jean-Francois Hamel and graduate student Rachel Morrison. Photo: Submitted

Sea cucumber conservation

Dr. Mercier and her co-authors highlight that sea cucumbers "paradoxically suffer" from being highly prized in Asian cuisine and traditional medicine, which leads to overexploitation, and being commonly disregarded due to their non-charismatic nature, resulting in inadequate study and protection.

The paper emphasizes that despite the rich diversity within the class Holothuroidea, sea cucumbers are often managed uniformly in fisheries a practice that overlooks significant species-specific differences.

This generalized management approach has contributed to the endangered status of many sea cucumber species and the collapse of wild populations.

In the spring, sampling is carried out through the ice with the help of local partners. Pictured is Sanikiluaq resident Sala Iqaluq (front) using a long pole net to collect benthic organisms while graduate student Sara Jobson collects a water sample in Sanikiluaq in 2023. Photo: Submitted

While calling for urgent action to address the main threats to sea cucumbers, including overfishing, poaching and trafficking, the paper also notes the strong governance, including leadership and guidance from Indigenous communities, that exists in Pacific Canada.

Dr. Mercier is hopeful that governance models inclusive of Indigenous leadership can be extended to fisheries occurring in the North Atlantic and Arctic.

Collaboration with Indigenous communities

Dr. Mercier says the team's Nunavut field expeditions are contributing to a greater understanding of sea cucumbers and other benthic organisms while building relationships with Indigenous communities in the North.

The Mercier lab has been holding workshops with the Paatsaali High School in Sanikiluaq, Nunavut, where representatives of the Arctic marine fauna are being examined and discussed. Photo: Submitted

The research team works closely with local Inuit organizations, such as local high schools and Hunters and Trappers Associations in Nunavut, to share findings and gain valuable insights into the Arctic marine ecosystem as a whole.

"It's a multidirectional pattern of development," Dr. Mercier said, adding that the researchers often participate in community activities and give presentations to exchange knowledge and discuss ongoing research.

"The research we do would not have the same quality or impact without the guidance and knowledge of local Inuit team members," said Sara Jobson, a PhD student in the Mercier lab. "It has become really important to me that we continue learning how to decenter our Western perspective on science and let Indigenous groups who live on the land inform the work."

The collaboration has proven essential to understanding the role of sea cucumbers among other species in Arctic ecosystems and providing guidance on conservation practices.

During fall expeditions, when the sea is open, some of the research is conducted with the support of local boats. From left, Dr. Annie Mercier and post-doctoral researcher Dr. Joséphine Pierrat sample juvenile sea cucumbers on a freshly collected boulder in Kataaluq, Nunavut, in 2024. Photo: Submitted

Dr. Mercier says that Indigenous communities are often deeply involved in the stewardship of natural resources and highlights their knowledge about the region's ecology.

"Witnessing Indigenous practices and meeting community members such as hunters, crafters, elders and children to learn from them truly puts our work in perspective," said Méliane Deshaies, a graduate student in the lab. "Especially in conservation efforts and practices, Indigenous knowledge and guidance must be involved to efficiently protect biodiversity in polar ecosystems."

Science and community engagement

For Dr. Mercier, every discovery and conservation breakthrough is a collaborative achievement.

"Everyone gets quite excited," she said. "It's part of the contribution you make to science."

Beyond sea cucumber-focused fieldwork and new discoveries, Dr. Mercier and her colleagues are also dedicated to educational outreach, helping undergraduate and graduate students and Indigenous youth engage with Arctic marine research as a whole.

A project she leads at the Department of Ocean Sciences has received a little over $13,000 in TILE funding to add new educational materials in Brightspace, starting in the winter 2025 semester.

This new addition to the curriculum, titled Lighthouse Learning, includes a module on Indigenous perspectives and features case studies on ocean sciences fieldwork conducted in the North.

"I think community-based science is the way forward," said Yuthika Jalim, a master of science student who works in the Mercier lab. "The learning process is all-encompassing and highly enjoyable, and the opportunity to share skills and insights as well as understand Indigenous knowledge and perspectives definitely enhances the learning experience."