When Shaakira Gadiwan was a child, she loved walking around the house with a tiny hammer, building and fixing things. She carried her hammer, made from materials she found around the house, in a small tote bag decorated with stars.

"I would find a screw that fell from the dining chair, and I would put that in the bag like I was a tradesperson," Gadiwan recalls during a summer trip to the Kluane Lake Research Station in the Yukon with Dr. Emma Spanswick, BSc'02, MSc'04, PhD'09, an associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the Faculty of Science.

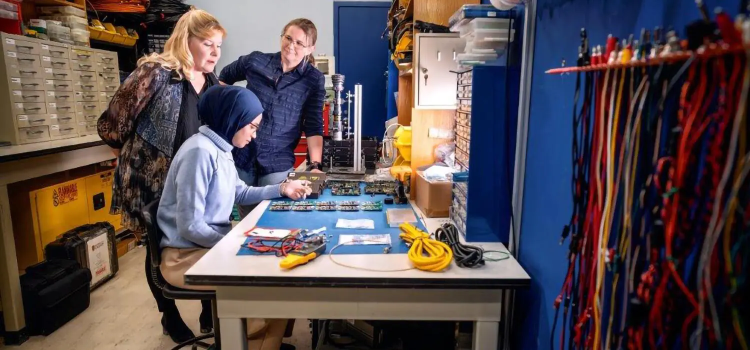

From left: Susan Skone, Shaakira Gadiwan and Emma Spanswick. Photo Courtesy Michele Ramberg

Perhaps it's no surprise then that Gadiwan, BSc (Eng)'25, is now a master's student in geomatics engineering in the Schulich School of Engineering at the University of Calgary.

Her practical skills, including using a hammer, came in handy last summer when she worked as a research assistant with the Space Remote Sensing Lab in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

As part of its Get Science Done strategic plan, the Faculty of Science is embracing "radical research collaboration" to drive groundbreaking changes in areas such as space science. It is providing students involved in the research with hands-on experiences in labs and off campus.

Installing and testing equipment in the field

During the field trip to deploy equipment, Gadiwan helped to install a ground-based remote sensor used to observe the near-Earth space environment.

"I think someone needs to use a hammer," Spanswick joked, as she handed her the tool.

Gadiwan was also on the August trip to test one of the lab's aurora cameras, called SMILE (Solar Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer), which takes pictures of the night sky every three seconds and is synchronized with 10 other cameras across Canada and Alaska.

"It's an all-sky imager, meaning it images with a fish-eye lens so you can see horizon to horizon," says Gadiwan. "It's a bit more than that, actually instead of 180 degrees, it's 185 degrees so, even if you are under the camera, you're captured."

An overnight test with the two pieces of equipment showed the team that they needed to make some adjustments.

"We learned that we were our own worst enemy," Spanswick explains the next morning. "The antenna in the field is picking a lot of high-frequency noise that's generated by the camera itself.

"That's one of the reasons we do these tests."

Spanswick, a Canada Research Chair in Geospace Dynamics and Space Plasma Physics, says the design of the instruments requires engineers such as Gadiwan, who's involved in the software development, and Lukas Vollmerhaus, BSc (Eng)'17, an instrument design and maintenance engineer in the lab.

"A lot of work goes into the mechanical, electrical and software systems to enable this camera to run in an autonomous way," Spanswick says. "It's quite the challenge, an engineering challenge, to get everything in place while also providing the data for science."

Dr. Susan Skone, PhD'99, a professor in the Department of Geomatics Engineering and associate vice-president (research) at UCalgary, says it's fantastic to be able to combine the expertise of both scientists and engineers.

"These problems are complex; we need the perspectives of everyone, we need this team that crosses disciplinary boundaries," she says.

Interest in engineering stems back to elementary school

Gadiwan, who's co-supervised by Skone and Spanswick as part of her master's program, saw her interest in engineering peak early.

Back in elementary school, she recalls having a homework project to build a structure using only two materials that could withstand 100 pennies.

"Glue counted as a material," says Gadiwan. "I took four pieces of yellow legal paper and made a triangular structure, using paper and glue."

Her teacher told her she should become a civil engineer.

"That stuck with me," says Gadiwan.

She went into engineering in her first year of university in 2020, which was held online because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gadiwan says learning how computers worked "made so much sense to me."

In her second year, she switched to electrical engineering.

She applied to work in the Space Remote Sensing Lab after stumbling across an internship opportunity from the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

"This is really cool," she recalls thinking at the time. "It's a broad range of interests outside of what my education was teaching me. It's multidisciplinary."

Following the internship, Gadiwan continued working in the lab as a summer student and still uses it as part of her master's program.

"The more I work with Emma's group, the more I want to stay here," she says.

The Kluane Lake Research Station (KLRS), located 220 km northwest of Whitehorse, Yukon, is on the traditional territory of the Kluane First Nation and the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. KLRS is operated by the Arctic Institute of North America, Canada's first and longest-running Arctic research institute.