Modelling the change in quantum computing

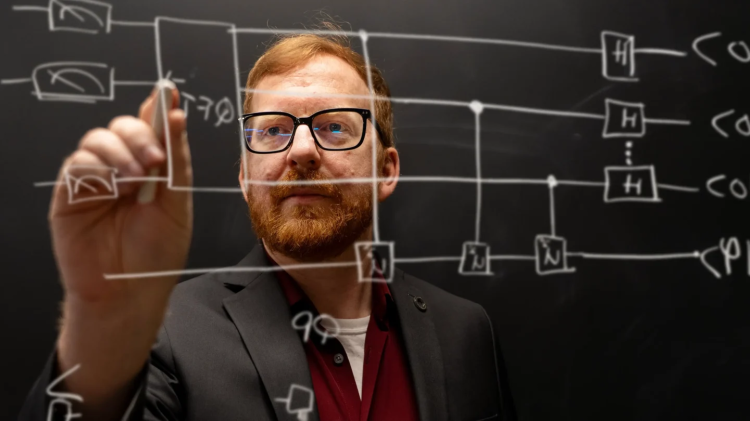

Thomas Baker, physicist, chemist and Canada Research Chair in Quantum Computing for Modelling of Molecules and Materials, is building Canada's quantum expertise. Although quantum theory is a century old, quantum applications are still fledgling. So, Baker is developing algorithms for materials and technologies that can simulate the benefits that scientists are aiming for in quantum computers the incomparable speed, the exceptional data capacity, the relatively modest physical size.

Thomas Baker of the departments of Chemistry and Physics holds a Canada Research Chair in Quantum Computing for Modelling of Molecules and Materials.

He intends to use the properties of quantum physics to greatly enhance our ability to make new devices for large-scale research uses. Historically, similar studies on classical computers have led to cell phones. These advances have the potential to accelerate research data processing, speed up real-world solutions like drug discoveries, and reduce energy use in computers for a cleaner future.

Baker is one of many University of Victoria (UVic) professors who supports unique training experiences for graduate students in quantum computing hardware and software. Students are immersed in some of the most cutting-edge quantum research including algorithms for quantum chemistry, methods for designing qubits, error correction and materials with suitable properties for quantum computing.

One of his students, Anne Najdzionek, has been selected for the QV Studio Validate entrepreneurship program. This Canadian venture startup builder helps researchers and innovators turn advanced quantum technology ideas into viable startups.

My students are willing to take risks and try new things. The field of quantum is new enough that you can distinguish yourself by being creative. At UVic, we are dreaming about what's possible,"

Thomas Baker, Canada Research Chair in Quantum Computing for Modelling of Molecules and Materials

In pursuit of those dreams, Baker also leads UVic's 14-member interdisciplinary quantum research cluster, which supported the successful application for a $5-million Alliance Consortia Quantum grant. Led by UVic physicist Rogério de Sousa, chemist Irina Paci and engineer Tao Lu, the award funds a consortium of researchers from six universities and four industry partners to make quantum processing scalable and commercially viable.

The cluster has given quantum researchers at UVic access to policy- and decision-makers. This, along with UVic's Quantum BC partnership with the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University, was instrumental in DeepTech Canada holding the international Quantum Days 2026 conference in Victoria, drawing 400 people from seven countries on three continents to share information, enthusiasm and the human sort of quantum networking.

Building community through quantum connections

Hausi Müller, professor of Engineering and Computer Science, addresses the 2024 International Electrical and Electronics Engineers Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering. Credit: Brad Kasselman of Kasselman Creative

One of UVic's Quantum Days speakers, engineering and computer science professor Hausi Müller, is a master of creating nodes of interest and expertise. For the past 15 years, he has been a key figure in bringing quantum computing into the mainstream of engineering. He has created working groups and international conferences, most notably the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering. He chairs multiple boards and committees that advance the field of quantum. And that's in addition to leading research projects such as another UVic five-year, $5-million NSERC Alliance Consortia Quantum to develop Canada's distributed quantum computing capabilities, and a CREATE grant to train the next generation of quantum computing scientists.

"I know the community well," he understates. "My goal is to build a ginormous ecosystem."

In a sense, those human connections parallel the distributed software systems that are the focus of his research. In order to optimize their performance, reliability and scalability, they must be adaptable, adjustable and responsive.

"With quantum computing, you can now simulate things, chemical, biological or physical systems, quickly that were not possible to do before," he says. "In drug discovery, for example, you can play with molecules on your computer and generate a lot more data quantumly. You can use quantum science and generative AI together. We can shift data from quantum to the classical side to discover patterns. We can build round-trip engineering sandboxes to explore hybrid applications in the vast space between quantum science and classical generative AI.

"Quantum as a new model of computation is a vast field. It's very exciting. I still feel and I say this all the time like a kid in a candy store."

The sweet spot: a spectrum of quantum

Sarah Huber of UVic's Research Computing Services helped design and build the Arbutus Cloud computing facility.

Müller and Baker are just two of the many scholars who store, process and transfer vast amounts of data using the research computing facilities at UVic, assisted by people like Sarah Huber.

With expertise in high-performance computing for mathematics, Huber helps scholars at all stages, from undergrads to graduate students, post-doctoral fellows and faculty, to use advanced research computing for their projects. That includes people using Arbutus Cloud for quantum chemistry simulations, quantum physics, engineering biosensing and much more.

Huber is a key player on the team that designed, built and manages the Arbutus Cloud facility at UVic. With processing speeds thousands of times faster than a desktop computer, Arbutus Cloud is the cornerstone for more than 1,000 research teams across Canada and more than three million end-users worldwide.

"At UVic there's a range of expertise that touches on a lot of different areas of quantum," she says. "It's helpful for science and for society to have those different perspectives and many different areas coming together. Hopefully, it will help drive research in new directions."

New rules for the (quantum) game

Benjamin Anderson-Sackaney, UVic Department of Mathematics and Statistics.

As a pure mathematician, Benjamin Anderson-Sackaney solves problems that develop mathematics itself.

"Mathematics is, in a way, a gigantic game where we start with some basic rules and see what kinds of moves we can make," says Anderson-Sackaney. "We find new moves and then see what new moves we can make from those."

One of those ever-advancing moves is quantum group theory.

"I work on seeing what parts of groups can be explained in terms of quantum groups and what new things quantum groups can do that ordinary mathematical groups cannot," he says.

To demonstrate, he shuffles a deck of cards. The quartet he plays face down is one permutation of possible four-card groups. If he were to shuffle the deck again, he'd get a different permutation of four cards. The collection of all permutations is called a group. When you're dealing with groups, he says, you know some properties and you try to understand their properties in another context.

He turns over the five of clubs, then the three of hearts. Turns them face down again before flipping the three and then the five.

"Each card is the same whether you flip it over first, second or last," he says. "But in quantum mechanics, the sequence that you turn over the cards matters. Each flip is an observation and the order of observations gives different results."

Very few universities in North America work with quantum groups in the context of operator algebras perhaps three in Canada. By bringing his expertise to UVic, Anderson-Sackaney has dealt the university some strong cards.

However, he's joined a scientific and engineering community that has been advancing the (quantum) game for years.