Most people take for granted which hand they use to reach for a cup of coffee or a puzzle piece. However, a new study out of York University suggests that for autistic individuals, which hand they use for various tasks is highly variable, which points to profound differences in the brain.

The research, published today (Jan 19) in the journal Autism Research, found that even autistic adults who are right-handed demonstrate a reduced specialization of hand use and more distinctive movement patterns when compared to non-autistic peers.

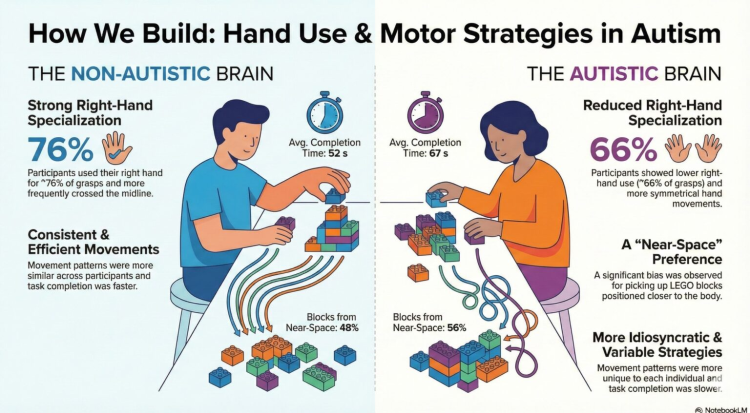

"Handedness is one of the most visible markers of how our brain's left and right hemispheres specialize for different tasks," says York University Associate Professor Erez Freud, who conducted the study with lead author and Master's student Emily Fewster. "In the neurotypical population, about 90 per cent of people show a strong right-hand dominance, reflecting the left hemisphere's specialization for fine motor skills. Our study shows that in autism, this specialization is less pronounced, leading to a unique and highly individualized motor signature."

The LEGO Building Task

To observe these behaviors in a real-world context, researchers asked 54 right-handed adults, half with an autism diagnosis, to recreate complex LEGO models. Unlike traditional questionnaires that ask which hand someone uses to write, this naturalistic task allowed researchers to track thousands of dynamic movements in 3D space.

By analyzing how people actually move during the LEGO building task, researchers found that the right-handedness of autistic participants' function quite differently than that of the non-autistic participants. Despite both groups identifying as right-handed, the autistic participants used their right hand much less often for grasping and did not show the typical dominant preference for using their right hand when reaching across their body.

The autistic participants also tended to shrink their workspace by focusing on blocks placed closer to them, suggesting a more cautious or individualized strategy for managing the space around them. In addition, their movements followed highly unique, idiosyncratic paths. While non-autistic participants tended to follow a similar sequence of actions, each autistic participant moved in a distinct, more variable way.

Together, these findings suggest that the autistic brain organizes movement in a less specialized, more variable manner than previously understood.

Implications for Earlier Identification

While the study focuses on brain organization, these "motor signatures" have significant clinical potential. Because motor skills often emerge in infancy, long before the complex communication skills typically used to diagnose autism, identifying these subtle motor differences could open a window for much earlier support.

"Standard questionnaires often miss these nuances because they don't capture the dynamic nature of real-life movement," says Freud. "By looking at how people actually move in a natural setting, we can identify objective markers that might eventually help us provide more tailored support strategies much earlier in development."

The researchers suggest that this "noisy" or variable motor processing supports the theory that autism involves broader, less specialized neural representations across the brain.