"I never in my whole life would have imagined being part of a process of informing brain injury policy development in Canada," says Mauricio Garcia-Barrera, professor of psychology and director of the CORTEX Lab at the University of Victoria (UVic). "It's incredible."

Garcia-Barrera travelled to Ottawa in November, as part of a delegation to generate support for Bill C-206 An Act to establish a national strategy on brain injuries.

UVic brain injury research team with hosts and research collaborators in Haida Gwaii, 11 April 2025. Photo credit: Tori Dach, Cridge Centre for the Family.

The private member's bill, sponsored by member of Parliament Gord Johns for Courtenay-Alberni, calls for the government to develop a national strategy to support and improve brain injury awareness, prevention and treatment. This includes supporting rehabilitation and recovery for persons living with brain injury.

"Stigma, siloed service systems, lack of funding, diagnostic failures, inadequate housing models there are so many barriers to care for people with acquired brain injuries in Canada," says Garcia-Barrera. "Especially for people who are unhoused and those who have experienced opioid toxicity and/or intimate partner violence."

His research team spent three years conducting participatory action research locally, to develop a BC Consensus on Brain Injury, Mental Health and Addiction gathering the perspectives of survivors, health-care workers, frontline service providers, government representatives, family members, researchers, Indigenous people and other equity-deserving groups from across the province.

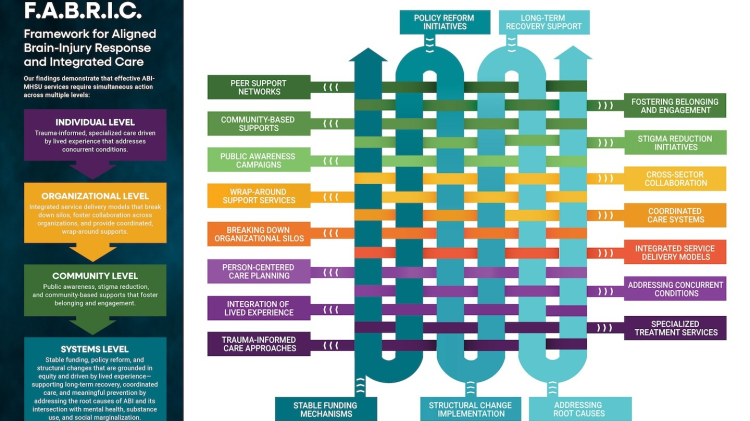

The published results include a new Framework for Aligned Brain-Injury Response and Integrated Care (FABRIC), integrating policy reform with long-term recovery support.

"We also developed a phenomenal tool called Decision Map," says Garcia-Barrera. This tool gathers the evidence on brain injury interventions, in the context of mental health and substance use, and identifies the gaps.

We hope our research will guide researchers, funding agencies, and the government to develop more effective support for brain injuries."

Mauricio Garcia-Barrera, professor of clinical neuropsychology

F.A.B.R.I.C Framework for Aligned Brain Injury Response and Integrated Care.

From Colombian gold mines to the streets of BC

Garcia-Barrera, a native of Medellin, Colombia, has always leaned towards social justice. His undergraduate thesis at the University of Antioquia investigated the neurotoxic effects of mercury exposure in gold mine workers.

It is perhaps not surprising then, that his interest in executive functioning brain processes that help us plan, remember, and carry out tasks effectively led him first to studies of concussion and other acquired brain injuries, then to the context of mental health and addictions.

Janelle Breese Biagioni was one of the catalysts for this evolution. Founder of the CGB Centre for Traumatic Life Losses and executive director of the BC Brain Injury Association, Breese Biagioni knows the impact of acquired brain injury personally. She lost three loved ones her brother, husband and a close friend to brain injuries within an 18-month period. She is now a fierce advocate for survivor care and was named 2025 Disability Changemaker of the Year by March of Dimes Canada.

Breese Biagioni invited Garcia-Barrera to team up on a grant application, researching the intersection between brain injury, mental health and addictions. Together they devised a three-year community-engaged research project, investigating how best to support survivors. The research focused on overdose survival in year one, intimate partner violence in year two, and housing and homelessness in year three.

"There's great research on mental health," says Garcia-Barrera. "There's great research on brain injury. There's great research on substance use and addiction. But many people face all three simultaneously, and the system has been designed to compartmentalize them."

Thanks to funding from the former BC Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions and The Vancouver Foundation, the BC Consensus on Brain Injury project was born.

The work has subsequently been supported by funding from Michael Smith Health Research BC and Mitacs, and by partnerships with organizations including The Cridge Centre for the Family, CGB Centre for Traumatic Life Losses, BC Brain Injury Association and Nanaimo Brain Injury Society.

"The BC Consensus makes explicit what has been ignored for far too long," says Breese Biagioni. "You cannot separate injury from the conditions that shape a person's safety, dignity and recovery.

When systems silo care, people fall through the cracks. This BC Consensus calls us to repair those cracks not with promises, but with coordinated action grounded in human rights."

Janelle Breese Biagioni, executive director, BC Brain Injury Association

Opening ceremony of BC Consensus on Brain Injury, Mental Health and Addictions annual meeting at UVic, 2024. Pictured left to right: UVic provost Elizabeth Croft, Cole Kennedy (UVic), Julia Schmidt (UBC), Jennifer Whiteside, former BC minister of mental health and addictions, Mauricio Garcia-Barrera (UVic), Erica Woodin (UVic), Janelle Breese Biagioni. Photo credit: Jason Guille, Sunset Labs (Victoria, BC).

Indigenous community engagement

From 2022 to 2025, the research team convened a series of annual consensus building days. The team includes UVic co-investigator Erica Woodin and PhD student Cole Kennedy, as well as University of British Columbia co-investigator Julia Schmidt and PhD student Jasleen Grewal.

They invited hundreds of stakeholders from across BC to attend events at UVic, and at satellite locations in Nanaimo, Kelowna, Terrace and Haida Gwaii.

The first event opened with remarks from Sheila Malcolmson, who was then minister of mental health and addictions, who acknowledged the systemic gaps in brain injury care.

Survivors, Indigenous support workers, neuropsychologists, police officers, therapists, harm reduction workers, policy makers and doctors came together to listen to panelists, engage in discussions, and contribute to priority setting.

"We travelled to work with members of the Haida Nation for three days," says Garcia-Barrera. It was an incredible experience, learning from them."

Members of the Haida Nation experience similar issues stigma, invisibility, siloed services amplified by the unique context of a remote community, with the history of colonial oppression and intergenerational trauma.

"My hope is that brain injury research begins to reflect Indigenous experiences, not overlook them," says Kym Edinborough-Capuska, transition house director for the Haida Gwaii Society for Community Peace.

Here on Haida Gwaii, the challenges are different: distance, housing shortages, lack of specialized care, and the impacts of colonization on Haida families and bodies."

Kym Edinborough-Capuska, transition house director, Haida Gwaii Society for Community Peace

"Policy needs to recognize that healing takes time, culture, and community. If this project can help decision-makers understand what supports truly work for Haida people. Then the work will carry forward in a good way."

Drug toxicity and brain injury: A vicious cycle

The first consensus building day at UVic focused on the cycle of drug toxicity and brain injury.

"During a toxic drug event, you experience respiratory depression and lack of oxygen to the brain," says Garcia-Barrera. "After three minutes, your brain cells start struggling for survival and after five minutes those cells start dying.

"When people come back from opioid poisoning, often there is brain damage. It may be very minor. But we are talking about hundreds of thousands of people who have survived drug poisoning, at an estimated rate of 15 to 20 per fatality.

"Now if they struggle with addiction and mental health challenges, there is a higher chance they will experience drug poisoning again. Then the brain injury might impair their executive functioning enough that they lose their job or their home. Without integrated care, maybe they sink deeper into depression and addiction. The cycle gets worse, and we need to break it."

Intimate partner violence: An invisible crisis

The most pervasive barrier is the "invisible nature of brain injury," says Garcia-Barrera. "When we think of brain injury, people imagine being in a major car accident, breaking their neck, and ending up in a wheelchair. But these are the least pervasive brain injuries. Most brain injuries are mild."

Intimate partner violence events, such as strangulation, can often result in such mild injuries, which are complicated by trauma.

If a victim struggles to leave an abusive relationship, then there may be repeated injuries, along with stigma, spiraling mental health and addiction struggles. If they do leave, they may be dealing with a brain injury alongside housing insecurity or homelessness.

Research shows that more than half of people experiencing homelessness have a history of traumatic brain injury, with most of them acquiring the injury first. Research also shows that people are more likely to become brain injured while experiencing housing insecurity.

Contributing to the invisibility of brain injuries is the fact that symptoms are often misinterpreted in medical or service settings. "If people are belligerent, or aggressive, it may look like they are high or drunk, rather than brain injured," says Garcia-Barrera.

"The system is very fragmented. There is a lot of gatekeeping. Services are very siloed. And in BC there is no integration of medical records."

Policy reform and integrated care

The good news is that integrated and coordinated care models can break down the siloes effectively. Interdisciplinary teams can offer wrap-around support, and prevention and awareness campaigns do make a difference.

The BC Consensus on Brain Injury has created an integrated framework (FABRIC) that tackles the challenge of brain injury care on multiple levels.

At the individual level, it requires trauma-informed and specialized care, driven by lived experiences. At the organizational level, it demands integrated delivery models of wrap-around support.

At the community level, the framework promotes public awareness and stigma reduction. Finally, at the systems level, brain injury survivors urgently need stable funding, structural change and policy reform.

And this is how Mauricio Garcia-Barrera found himself travelling to Ottawa in November 2025, to support the passage of Bill C-206.

"This has been a shift in my whole career," says Garcia-Barrera, who was named one of the Top 10 Most Influential Hispanic Canadians in 2022 a prestigious national recognition program that celebrates leadership, achievement, and impact within Canada's Hispanic community. "From neuroimaging in experimental and clinical neuropsychology to community-based engaged research, and then to Ottawa. Wow. It has opened so many doors!

"I hope the work results in much-needed changes to brain injury care in Canada."

Learn more about the CORTEX Lab.

Learn more about the BC Consensus on Brain Injury project.