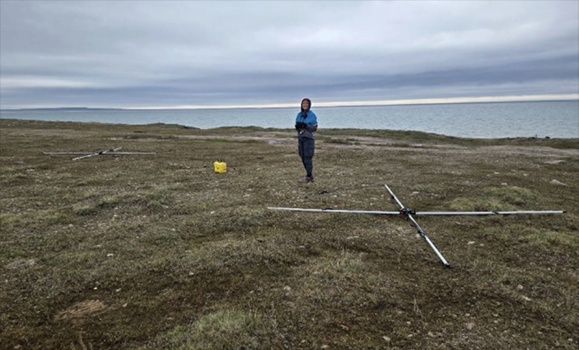

Dal researcher Bay Berry conducts a geophysical survey to map groundwater, ice, and subsurface layers up to 100 metres deep. (Submitted images)

The Arctic is often thought to be a frozen, impermeable region with no groundwater. However, the upper layer of the permafrost thaws in summer, forming a shallow aquifer and allowing unfrozen groundwater to be stored and routed to rivers. So, the warmer the summer, the larger the unfrozen zone becomes where groundwater can flow.

Using maps of climate, soil properties, topography and permafrost, scientists were able to show that most shallow Arctic aquifers today are slow draining, keeping groundwater close to the surface and promoting wet surface conditions and associated ecosystems.

Shifting groundwater impacts

Bay Berry, a PhD candidate in Dalhousie's Coastal Hydrology Lab, led the research initiative that shows that warming and changes to rain patterns could shift groundwater patterns. Those changes could promote deeper water tables and dry over five per cent of the Arctic land area, while an additional 11 per cent of the land area is projected to have higher water tables leading to wetter landscapes.

The amount of water that is stored or transmitted through an area can reshape ecosystems, carbon cycling and freshwater resources. In coastal areas, sea-level rise will further raise the water table in addition to increasing the impact of saltwater intruding into the aquifer.

Collecting data in the Arctic can be challenging for researchers, who are often limited in time and ability to transport materials.

"This project focused on using open-source data to characterize shallow aquifers across the Arctic," says Berry. "We found that across multiple climate models, there is high agreement that some areas, such as Alaska, will transition towards shallower groundwater flow and wetter landscapes. Other areas, like much of western Siberia, will have deeper water tables and dryer surface conditions in the future."

Future Arctic impacts

The authors say that changes to the physical and environmental factors that control aquifers will change how water flows through and is stored in Arctic watersheds.

The researchers outlined their findings in a study published in Environmental Research Letters.

"Changes to northern aquifer systems matter because they control how rain and snowmelt are conveyed through Arctic landscapes and can influence soil moisture and vegetation," says co-author Dr. Barret Kurylyk, associate professor and Canada Research Chair in Coastal Water Resources.

"Because aquifers and groundwater flow patterns strongly influence where wetlands occur as well as river flow, these findings have implications for the future distribution of surface water and reliant vegetation and animal species in northern landscapes."

In cold regions, streams can be blocked by snow and ice until mid-summer, limiting the flow of water towards the ocean.

Berry says the research highlights where change is most likely to occur, as well as regions of high uncertainty where better data is needed to understand the rapidly changing Arctic.

"Through this framework, we mapped out the majority of Arctic aquifers as favouring local flow and wet landscapes under present conditions, but these types of aquifers will, on average, become less widespread due to projected climate change," says Berry.